Happy Monday everyone,

Thank you for subscribing to Wu Fei’s Music Daily. This is episode #481 — Sweeping round and round 七月的北斗.

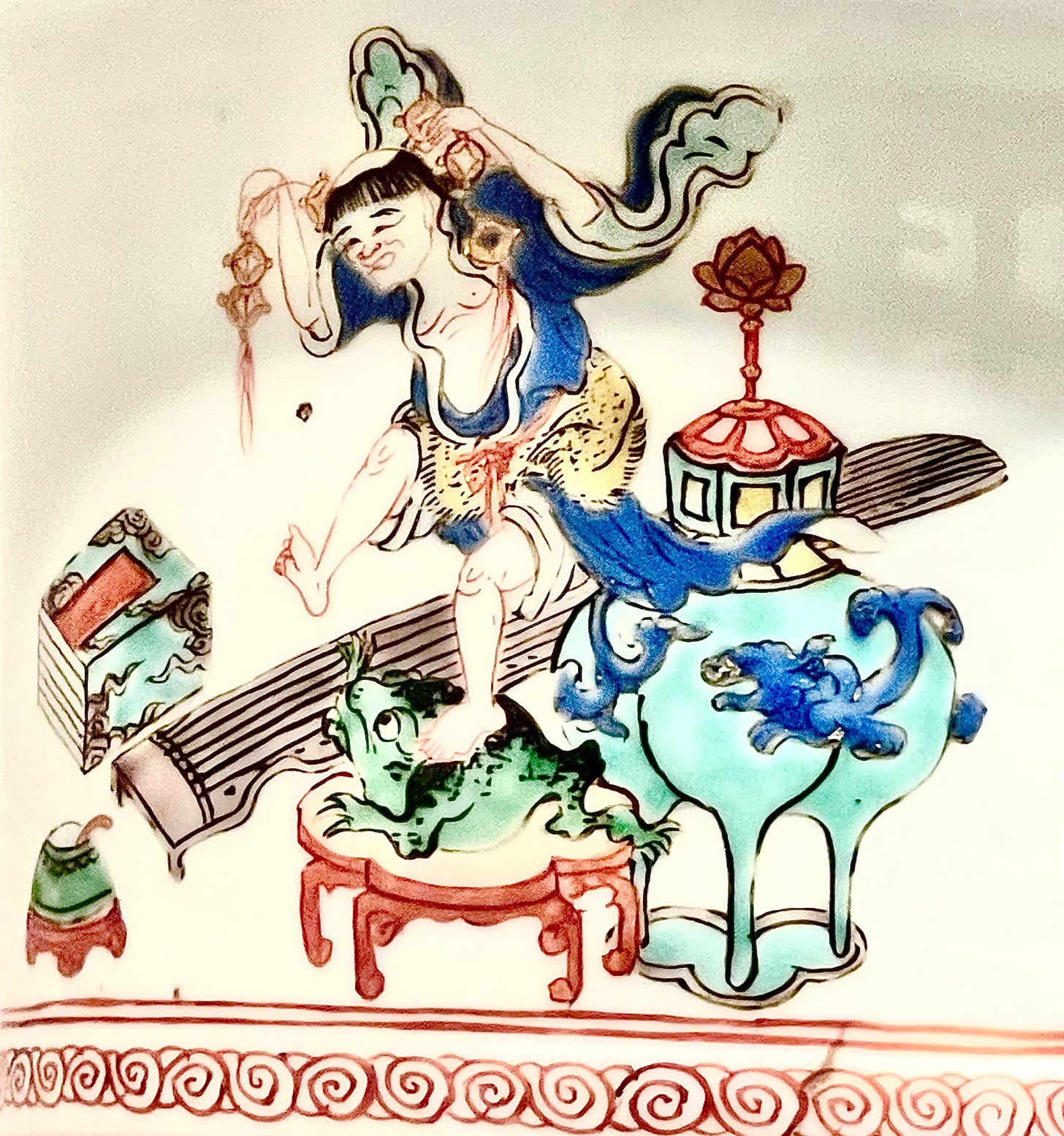

This piece was created yesterday on multitrack guzheng, performed by me. The inspiration was from a painting on a ceramic vase (photo below) that I saw in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City recently. It was from the Qing Dynasty (1644- 1911) period. The vase was quite big, at least 3 feet tall. The picture below was on the neck area of the vase. I was excited to see the zither (like the guzheng) painted on the beautiful vase. It was such an incredible piece of art!

I’d like to share the description I read for the ceramic section at The Met:

“Ceramics, Science, and Scholarship

Chinese appreciation for the ceramics began in the either century, when certain wares were extolled for their beauty and for their appropriateness for drinking tea. Study of ceramics was further refined in the eighteenth century when scholars such as Tang Ying (1682-1756), supervisor of the imperial kilns at Jindezhen 景德镇 who was spurred by contemporaneous interest in the study and classification of many topics, published five seminal volumes on the history and production of porcelain. One of Tang’s foreign friends was Pere Francois-Xavier Dentrecolles (1664-1741), a Jesuit priest assigned to open a church in Jingdezhen. Dentrecolles, who also translated Chinese accounts of medical practices and remedies and tea and silk cultivation,, wrote lengthy letter on the manufacture of porcelain, the first Western descriptions of the production of this material. Written in 1712 and 1722, these descriptions contributed to the development of Europe's own porcelain tradition, which began in 1708 in the German town of Meissen, thanks to the work of Johann F. Bottger (1682-1719) and Ehrenfried W. Von Tschirnhaus (1651-1708), both of whom had trained in the rapidly developing European scientific tradition that marked the Age of Enlightenment.

In Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, scientific analysis of Chinese porcelain paralleled aesthetic appreacition. Many of the terms used in Western languages to catalogue Qing-dynasty (1644-1911) porcelains are based on the work of the writer and collector Albert Jacquemart (1808-1875). Jacquemart, who published a history of ceramics in 1873 that included discussions of Babylonian, Egyptian, and Greek and Roman ceramics, divided Chinese porcelains pained with colored enamels into families based on the predominant color in the decoration. For example, porcelain in whihc green dominates is termed famille verte (green family) , while ceramics in which pink tones prevail are famille rose (pink family). Evocative French terms are also used in Western scholarship to describe the elegant monochrome glazes that cover later porcelains, such as claire-de-lune (moonlight) for a blue/grey glaze. Chinese scholarship uses different terms to describe the palette of enamels and the colors of glazes. For example, porcelain painted with enamels over the glaze are generally known as susancai (plain three colors), while those in which pink tones are dominant are sometimes catalogued as yangcai (foreign colors) or ruancai (soft colors); the Chinese term for the moonlight glaze is tian lan, or “heavenly blue.”

Wu Fei 吴非

Wufeimusic.com

Twitter @wufei

Facebook @realwufeimusic

Instagram @wufeimusic

YouTube @wufeimusic